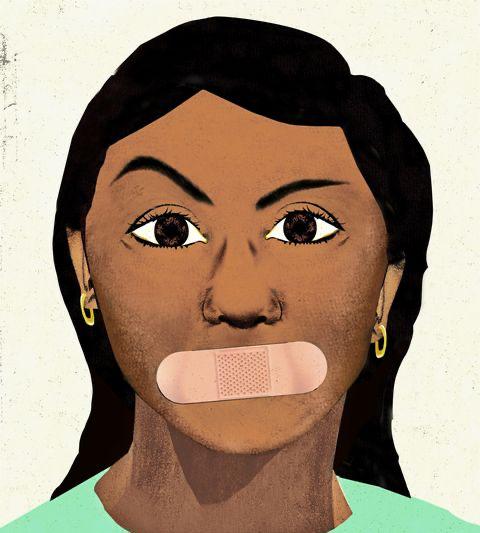

Discrimination and Racism in Mental Health Care

-By Sania Patel

The Collins dictionary describes mental health care to be services devoted to the treatment of mental illness and the improvement of mental health in people with mental disorders or problems. As with all health care services, it is expected to fall underneath the overall understanding of helping all people, however, recent studies and situations have proven that this may not be the case. Health care services, especially mental health care services, are often neglected due to lack of insurance, money, or time.

A study by health care professionals, Bryan Leyva (B.A), Alexander Persoskie (Ph.D.), and Jennifer M. Taber (Ph.D.), recorded that out of 1,369 participants, 24.1 percent neglected health care due to high cost, 8.3 percent because of no health insurance, and another 15.6 percent due to lack of time. However, unlike the participants who avoid health care due to personal circumstances, there are many more people who are greatly affected by outside situations. The outside situation is one caused by the health care professionals themselves - racism and discrimination.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) found several examples of racism and discrimination prevalent in the access and treatment of minorities seeking health care. The HHS found that, in 2014, around 20% of Black adults could not access health insurance compared to 10% in white and Asian adults. For Latinx adults, this figure was 35%. A 2012 study also found that predominantly Black zip codes were 67% more likely to have a shortage of primary care physicians (PCPs). Another study in 2016, found that many white medical students wrongly believe Black people have a higher pain tolerance than white people. The study recorded 73 percent of the participants had at least one false belief about the biological differences between races. There are several other health sectors where minorities are mistreated based on personal beliefs or false influences, such as chronic illness, cancer, and, most notably, mental health.

According to Mental Health America (MHA), “mental illness rates are roughly equivalent between some marginalized groups and white people. However, there are some significant areas of difference, such as: disability, schizophrenia, and addiction. The MHA reports Black people to experience a disproportionate amount of disability from mental health issues compared to white people. Black males are also four times more likely to receive a schizophrenia diagnosis than white males, as MHA suggests that many clinicians can overlook the symptoms of depression and focus on psychotic symptoms when treating Black people, due to inherent bias. To focus more on discrimination, the MHA reports that Native and Indigenous Americans to have the highest alcohol dependence rates out of any marginalized groups, while Asian Americans may be under-diagnosed. A 2016 study suggests doctors are less likely to diagnose alcohol addiction in Asian Americans compared to white people despite having the same symptoms. This disparity may occur due to the “model minority” stereotype, which frames Asian Americans as responsible and successful.

Through the evidence given by the MHA and HHS, implicit bias often negatively affects the mental health care treatments of marginalized groups. Discrimination and racism are the least mentioned, yet, given the statistics, arguably one of the most important factors of poor health care among certain groups.

The goals of mental health care are vast, however, as seen with previously mentioned studies, not always promised. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, mental health care focuses on the prevention, screening, assessment, and treatment of mental disorders and behavioral conditions. The Mental Health and Mental Disorders objectives also aim to improve health and quality of life for people affected by these conditions. This statement is then preceded by contradicting evidence. Following this, the U.S Department of Health and Human Services writes,

“Mental disorders affect people of all age and racial/ethnic groups, but some populations are disproportionately affected. And estimates suggest that only half of all people with mental disorders get the treatment they need.”

Racism and discrimination are the biggest problems in mental health care, as they cause avoidance and misdiagnosis for many people. Overall, systemic racism is a form of racism that is embedded in the laws and regulations of a society or an organization. It manifests as discrimination in areas such as criminal justice, employment, housing, health care, education, and political representation. System racism, in relation to medical care, directly translates to, people of color and those belonging to other marginalized ethnic groups who do not receive the medical care and support they need. Professor Hannah Bradby, a sociologist at Uppsala University in Sweden explains in more detail,

“The distinction between individual and institutional racism arose with the Black power movement in the U.S. when it was described as subtle and less identifiable compared with individual racism. ‘Respectable’ individuals can absolve themselves from blame for individually racist acts but nonetheless ‘support officials and institutions that perpetuate institutionally racist policies.’”

A 2014 report conducted in the United Kingdom, highlights systemic racism in mental health care services, and the consequences it produces. The study found that although Black people had lower rates of mental illness than other ethnic groups, they were “more likely to be diagnosed with severe mental illness and […] three to five times more likely than any other group to be diagnosed and admitted to hospital for schizophrenia.”

The study also reported that the rates of involuntary commission to psychiatric hospitals were 2.2 times higher than the average for Black African individuals in the U.K., 4.2 times higher for Black Caribbean people, and 6.6 times higher for those who identified as “Black or another ethnicity.”

The report concludes that,

“Treatment is more likely to be harsher or coercive [for Black people] than that received by white service users and characterized by a lower uptake of primary care, therapeutic, and psychological interventions.”

Although racism is clearly apparent in mental health care services, discrimination has proven to be superior in the field. Discrimination is defined as the unjust or prejudicial treatment of different categories of people or things, especially on the grounds of race, age, or sex.

A study was done by Vickie M. Mays, Ph.D., MSPH, Professor, Audrey Jones, Ph.D., Ayesha Delany-Brumsey, Ph.D., Courtney Coles, MPH, and Susan D. Cochran, Ph.D., MS, Professor reports,

“Fifteen percent of California adults reported discrimination during a healthcare visit and 4% specifically during mental health/substance abuse visits. Latinos, the uninsured, and those with past-year mental disorders were twice as likely as others to report healthcare discrimination. Uninsured patients were seven times more likely to report discrimination in mental health/substance abuse visits. The most commonly reported reasons for healthcare discrimination were race/ethnicity for Blacks (52%) and Latinos (31%), and insurance status for Whites (40%). Experiences of discrimination in mental health/substance abuse visits were associated with less helpful treatment ratings for Latinos and Whites, and early treatment termination for Blacks.”

Given the evidence, the report concludes that people who have experienced negative mental health outcomes, such as treatment abuse, are the most likely to be discriminated against, as they may act as an image of insecurity for a certain mental health care practice. People were then discriminated against depending on race and ethnicity, as certain groups held inherently biased opinions and viewpoints over certain groups.

To conclude, discrimination and racism are the leading cause of poor mental health care among certain groups of people. Certain practices exclude, overdose, or undertreat certain patients, mainly depending on race and ethnicity. These medical professionals often ignore their inherent bias towards groups and diagnose them according to their beliefs - not their patient’s true opinions. As the need for mental health care services grow, it is important to educate future medical professionals on recognizing their personal bias, and, most importantly, listening to their patient’s needs.